What Was Then A Wheatfield

by Georgina Hahn

via WordPress

When it comes to the pedestrian experience, New Yorkers should expect noise and interruption. On my commute to NYU, I pass several work sites. Men, mostly, clang and bang on their machines. So, when a crew like any other de-installed Ai Wei Wei’s Good Fences Make Good Neighbors in mid-February, Washington Square Park took little notice. More machines, more noise, business as usual. The giant steel cage once occupying the arch became neat piles organized by forklifts. Was I a bad neighbor for standing there and watching?

The Chinese artist's project was part of marking forty years of The Public Art Fund in New York. An exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York, Art in the Open, highlighted some projects from the past. According to the museum’s website, it was during the 1960’s that public art shifted away from monuments and war memorials, and towards more conceptual and creative sculptures. Today, even the word sculpture would be limiting to describe the kind of projects staged in New York.

Before thinking about the past works presented by the exhibition, I ask this question: what is it about public works that makes them memorable? I asked my mother this question, and she recounted the west side of the Berlin Wall. In the free half of the city, people graffitied over the symbol of Soviet control. It was an intervention, a powerful subversion of an existing structure. Through the use of visual tactics, something terrible became a reminder for the prevailing human spirit.

This ephemeral expression is precisely what we remember in public art. The takeaway is a reminder: other humans are here, inhabiting this strange and beautiful space. Think about Tony Rosenthal’s Astor Place Cube, a downtown treasure known for engaging those willing to give it a turn. Strangers come together for no reason except for the joy of a rotation.

Public Art Director and Chief Curator Nicholas Baume commented on The Cube in a video produced for the museum’s exhibition. “A piece like that,” he said, “becomes a part of the community. We know that, because when it was taken away, people wanted it back. That is how you know a public work is successful, when the public absorbs it into their community.”

Even temporary pieces can create experiences that bring people together. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s piece The Gates (2005), though only installed for sixteen days, was an extraordinary reason for people to gather in Central Park. 7,503 orange gates lined the pathways of the park and created the appearance of a flowing golden river. Originally proposed in 1979, the artist couple persisted with multiple administrations before finally being granted permission in 2003.

This magical effect was a call for appreciation. Central Park is an obvious attraction of the city for tourists and locals alike, but this work was an invitation to enjoy the beauty of this urban oasis. Beyond its physical realization, this project had an incredible political life too. Christo and Jeanne-Claude persisted for its realization for twenty-four years. To finally let two artists make an impressionable impact on a public space, at the scale of the largest park in Manhattan, is quite revolutionary.

While New York is the alleged helm of liberated expression, making a physical (legal) impact on the landscape can be difficult. Unless you are an architect or a city planner, you have few opportunities to change the confines of the urban experience. This is why public art is so important. Civilians, individuals, and creatives can have an impact on their environment.

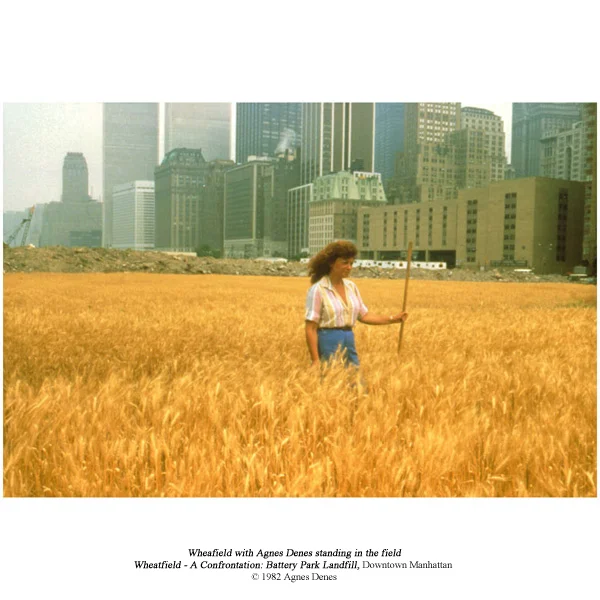

The feat of artist Agnes Denes has stayed on my mind since visiting Art in the Open. In 1982, two acres of wheat were planted and harvested in Battery Park. What is now a public greenspace was then a dumping ground for the land cleared for the World Trade Center. Her team cleared away acres of refuse to plant the field and eventually harvest wheat.

This piece tugs at my Hungarian reverence for bread. In the view of Wall Street’s stock brokers and paper pushers, Denes’ field went from dirt, to sprout, to wheat—an incredible juxtaposition for the “breadwinners” watching from their towers above.

The patience required for public art can range from months to years. At a discussion hosted by the museum, Performance and Protest in Public Art, Cuban artist Tania Bruguera commented on the temporal aspect often underestimated when engaging with society. "Society is slow," she said. “Six months is nothing in the life of a community.”

But this patience, this acceptance that art in the public won't always have an immediate effect is what can make practitioners like Bruguera revered in the communities they touch. “We can work in the future by being in the present,” she said. Works begin when the artists walk away, and even when they are gone, the piece has a life to live.

Originally published 03/09/18