The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

By Firozah Najmi

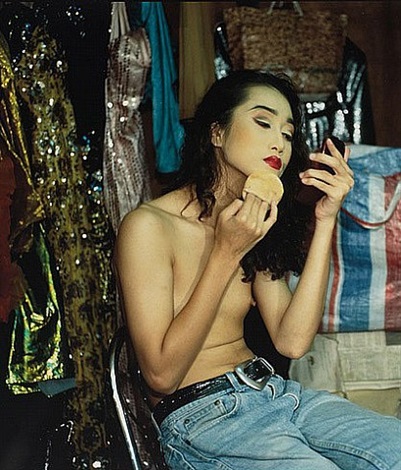

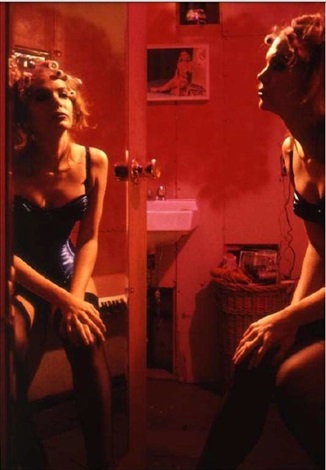

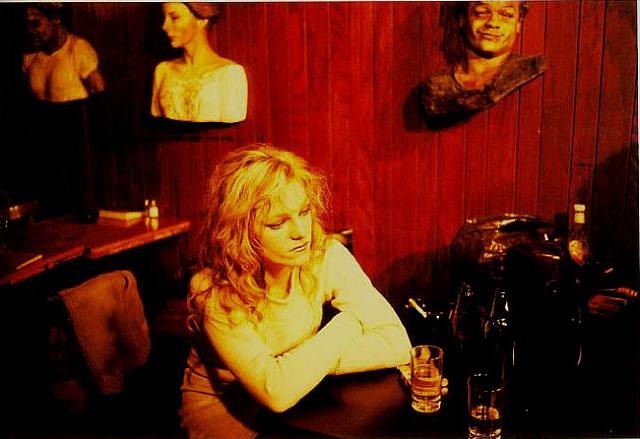

By skillfully exposing the rarely aestheticized aspects of the quotidian, Nan Goldin’s photographs are nothing short of visual poetry. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, an exhibition on display at the Museum of Modern Art through February 12th, 2017, is a brash encounter with the dark underbelly of companionship that brings pain, suffering, longing, and disillusionment.

Beginning with a series of poignant photographic stills, the exhibition climaxes in a 42-minute long slideshow. This twofold nature of the exhibition is a genius curatorial choice—the experience of viewing a still photograph on a sterile, white museum wall is drastically different from the flurry of images presented by Goldin in the form of the concluding slideshow. The video is roughly divided into broad themes, evidenced by accompanying songs, whose lyrics serve as commentary to the contents of the flashing photographs. Petula Clark’s “Downtown” rings rather unfittingly through the darkened theatre as photographs of drug paraphernalia and hazy studio parties flash on the screen—a dark, but thoughtful choice. Contextualizing Goldin’s long struggle with drugs, the famously upbeat melody lies in stark contrast with bleak visions of substance abuse. Furthermore, Goldin expertly conflates the need for a drug fix with the dependency found in a malfunctioning relationship.

Other images chronicle Goldin’s tumultuous relationship with a man only known as “Brian,” while some offer a voyeuristic look into the private, sexual lives of Goldin and her companions. We are arrested by moments of intense passion, left ruminating on images of thoughtful introspection. The sense of immediacy conveyed by the poorly composed imagery—the need to capture a fleeting moment at the cost of photographic conventions—is amplified by the sudden transitions between slides. Being that her photographs often cover hard-hitting topics, such as loss, the viewer is confronted with a rollercoaster of emotions; just as you begin to take in the contents of the photo before you, the image is stripped from your view to make room for a new one, perhaps demonstrating the painful, cyclical nature of unhealthy romantic relationships. Just as we become acquainted with the contents of one photo, it is pried from our grasp. This quality of the slideshow creates a high-intensity viewing experience largely uncharacteristic of still photography.

Goldin’s photography also raises questions about the nature of performativity in everyday life. Candid stills of Goldin’s friends caught in the throes of passion beg the question of how objective a medium photography can be. How forced are the performances of Goldin’s subjects? The act of photographing in itself is political: the choice of framing a subject, of deeming it important enough for capture, demonstrates the photographer’s intent and values. Goldin’s representation of her friends is undeniably moving. One wonders how the photographs appear so objective (resulting from their immediacy and their urgency) and yet still deeply appeal to the viewer’s emotions.

Voyeuristic, confrontational documentary photography is nothing new. But Goldin’s oeuvre offers something deeply compelling and unique to her practice. Beyond the blurry party shots and overexposed portraits lies something as fleeting as the moments she photographs—the ability to convey the complex nature of human relationships, especially of the flawed variety, in a universally comprehensible and heartbreaking way.

Originally published Fall 2016