Freeganism

By Kirsten Lootens

You look at your to-do list for the week, and begrudgingly scribble “grocery shopping” at the very bottom. You want to blink your eyes and have food appear in your cabinets because you know the line at Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods or Westside Market will be long, the receipt will show a number you’ll hate to pay, and some of the food you’ve paid for will end up being thrown away. One night, you pass by your regular grocery store, and there’s a worker in their bright t-shirt, lugging a huge bag of trash to the edge of the sidewalk. The bag tears and fresh fruits and vegetables, packaged cereals, granola bars, and loaves of bread pour onto the sidewalk. A couple of people stop and help clean up the mess, and you notice some of them place parts of the trash in their own bags. You get home and you’re still thinking about that bag of “trash,” and all that brightly colored produce. You open your fridge and notice that some of the fruits and vegetables you bought last week are also starting to go bad. You’ll have to throw them away soon. Why is there so much food that’s being thrown away?

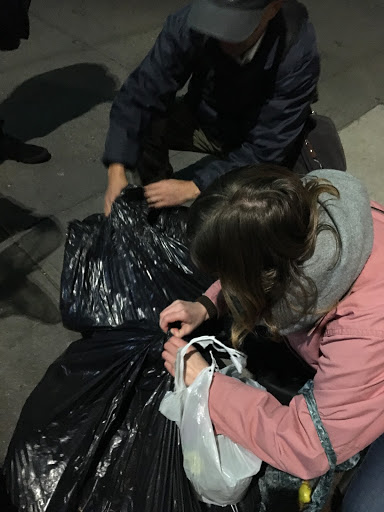

You look at your to-do list, and write “grocery shopping” at the top. Thursday night rolls around and you have your extra plastic bags that you’re trying to reuse, you’ve got comfortable walking shoes on, and you can see your friends waiting for you at the street corner. The streets are emptier than during the day and you all get started on your usual route. As you stop at different grocery stores, poking at the bags on the sidewalk with an expert hand, you laugh with your friends and make conversation with the store employees taking out the trash. At the end of the night you’re passing a grocery store you don’t normally stop at, and the trash bag rips, spilling food all over the sidewalk. You and your friends hurry over to help, laughing with the embarrassed worker and stuffing your bags with food you know you’ll use. You look up and catch the eyes of a young person walking by, her eyes are wide and confused. You try to smile but soon she is gone and you are back to digging for your meals. At home you are putting away the food you found, smiling at the thought of that girl. You hope she is thinking about waste, and you hope maybe she’ll look into ways of lessening her own.

Freeganism is not just a hobby. It’s more than digging through trash, as this anecdote might suggest. Freegans believe in creating as little waste as possible, and they do this by boycotting the economic system in place — one where profit motive has become more important than ethical considerations. Food waste is a massive problem in New York City, which sends about 1.5 million tons of food waste to landfills each year. So much of what is produced has negative environmental and social consequences. Freegans refuse to put any money into the capitalist system, instead rescuing products that have already been wasted. It’s more than a personal choice. Freeganism puts a strong focus on community and generosity. Members of this particular community cooperate with one another, making their searches social events, holding events for free swaps of items, and hosting walking tours for those that are interested. On the other hand, there are those that disagree with freeganism practices. Some see freegans as parasites, freeloading off of everyone else in society. These critics point out that freeganism actually depends upon the capitalist society that they are so strongly against. Another problem with freeganism is health and safety concerns. People see digging through trash as unsanitary, sometimes contaminated with rat droppings, household cleaners, or pesticides. Freeganism isn’t legal everywhere — a lot of cities and states have banned it, but Freegans continue to operate there, just more discreetly. In New York, however, Freeganism is legal and so it has a large following.

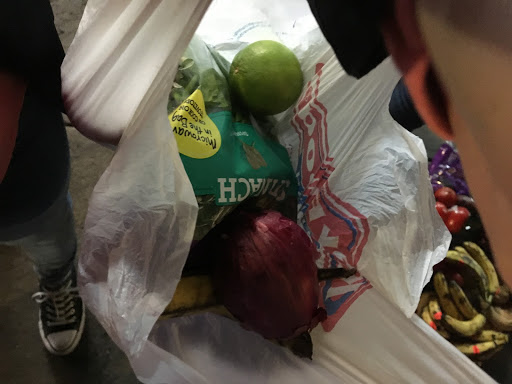

I went on a walking tour a couple of weeks ago offered to me through a professor. As someone who is environmentally conscious, I went in feeling skeptical. It felt strange to be standing outside of a grocery store, nine o’clock at night, poking trash bags and pulling food out of them. There were a lot of people on the walking tour that looked down on the food and refused to take any the whole time. By the end of the night, I had two bags of food. We found bananas, onions, spinach, limes, artichokes, and dozens of bagels. Gristedes on University Place had thrown out food that was just past the sell-by date, and much of it was still good. Bagels from Brooklyn Bagels and Bagel Bob’s are made and sold on the same day — they throw out the unused ones at the end of the night. When we got there right after closing, the bagels were not only still fresh, they were still warm. The initial reaction of disdain is natural, but you get over that soon enough when you see all this good food that’s being thrown away. First, you feel the outside of the bag. Experts like those who led our tour can almost always tell if the bag is mixed trash or if it’s just food. Once you think you’ve found a bag with food, you simply untie the top and start checking. If there’s nothing for you in there, or if it’s food mixed with actual trash, you tie the bag back up and move onto another one. Sometimes though, you find one with good food in it, so you take what you want, and then once you’re done you tie the bag back up. It’s hard to say no when you’re watching four other people pick up bagels and take a bite out of them, and once I tried it, I had no more qualms about it. I hated seeing how much gets wasted, and it made me really respect the Freegans leading our tour.

More than just an environmental movement, Freeganism is a social activity. The tour guides talked openly and endlessly about their experiences. They know the best nights of the week to go (Wednesday nights), which areas to stay away from and which to hit (grocery stores are better than smoothie shops). They taught us how to feel out a bag before opening it and showed us the correct was of reclosing it so as to keep up a good relationship with employees. It was a lot more work than regular grocery shopping. The tour guides told me that sometimes they don’t get home until midnight or even one in the morning. They had no complaints though — they like the camaraderie, how much money they save, and of course they love how much waste they’re able to prevent. Even if someone doesn’t want to go full Freegan, we can learn a lot from their lifestyle and what it means to be wasteful, as well as how this affects us and our environment. I was fed for the rest of the week and I didn’t spend a dime. The food we got wasn’t trash — it was just good food.