Let's Go Out

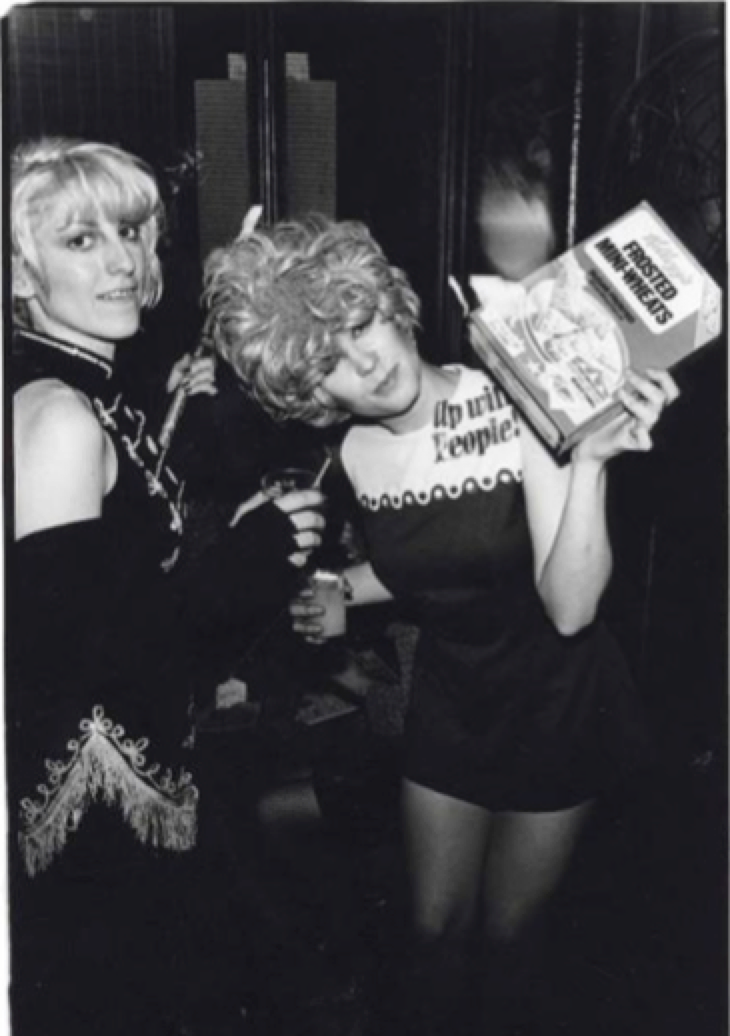

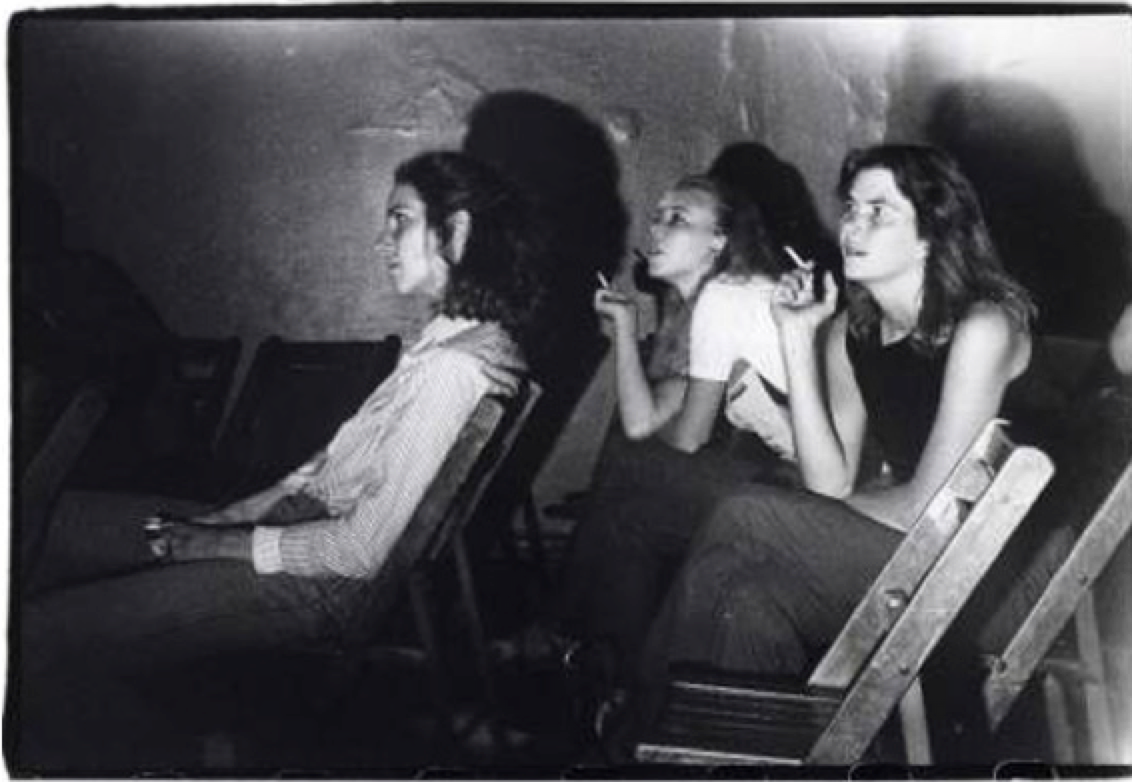

Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983

By Theri Anderson

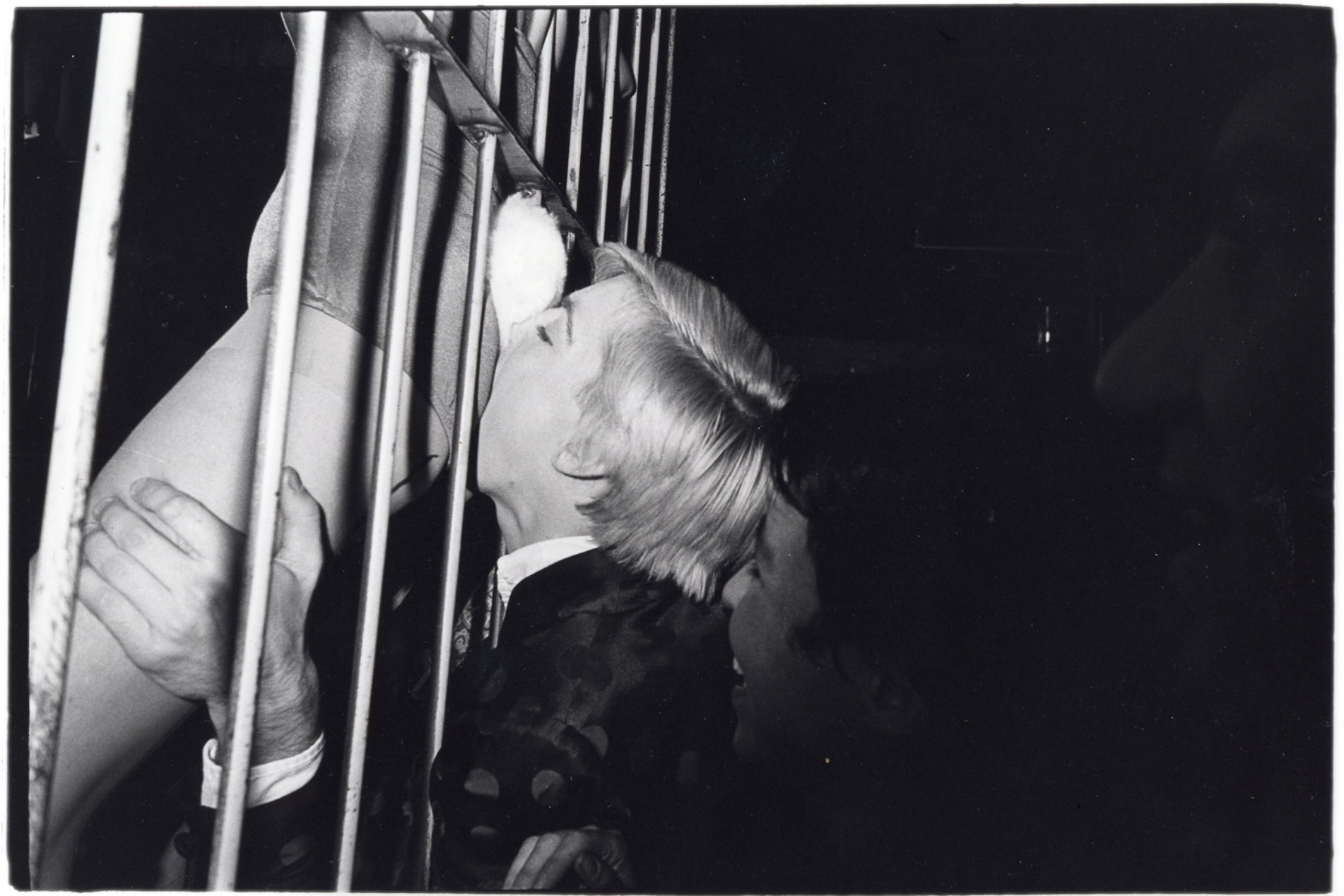

Image via MoMA

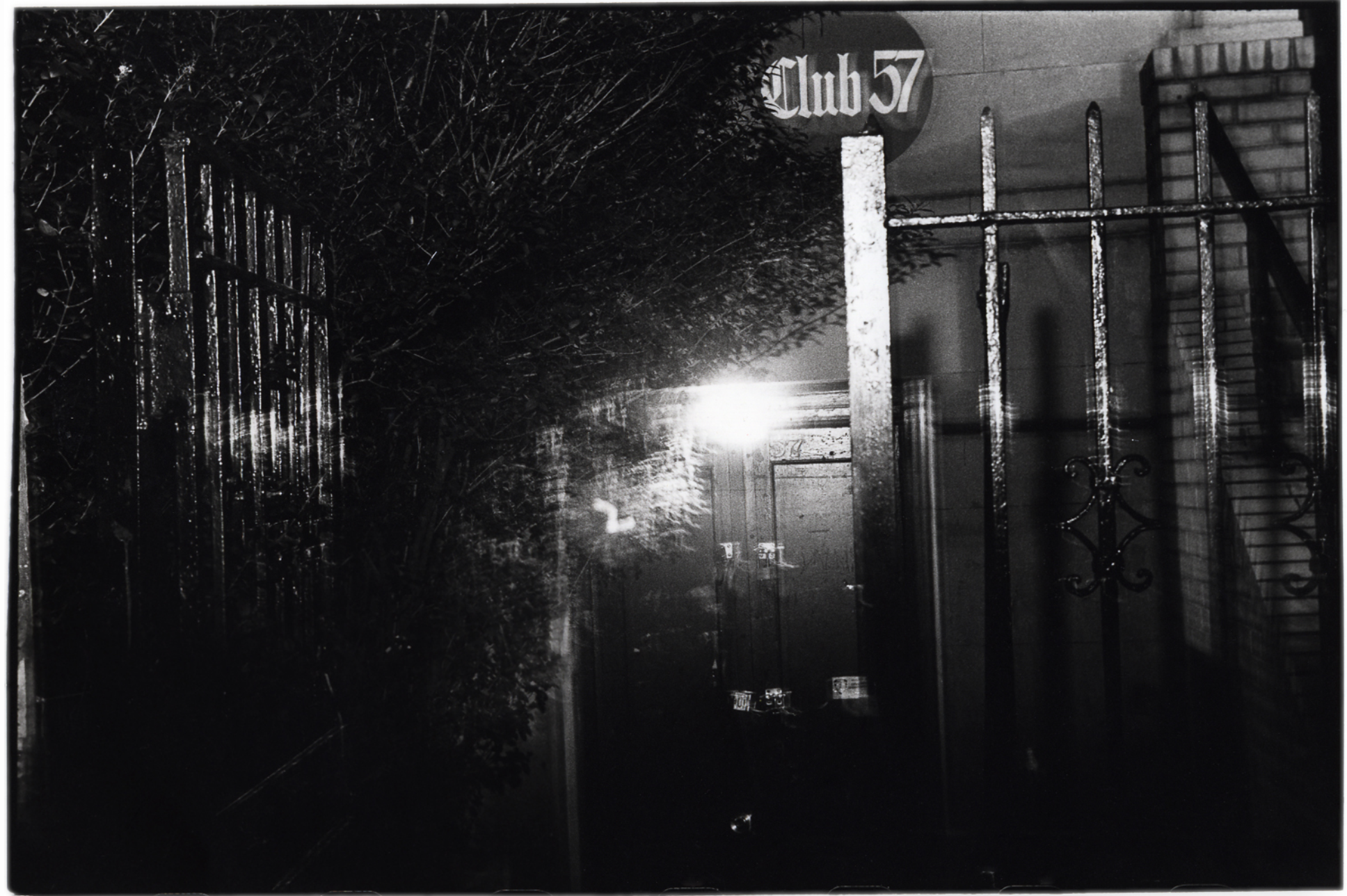

“This ain't no party, this ain't no disco, this ain't no fooling around. This ain't no Mudd Club, or C.B.G.B. I ain't got time for that now,” sings David Byrne of the Talking Heads in their classic “Life During Wartime.” Looking back, this song now memorializes some of the iconic New York City clubs of the 1970s and 1980s—and the Museum of Modern Art is doing the same with their new retrospective on Club 57. Located at 57 St. Mark's Place, Club 57 became an exotic club scene that artists including Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and John Sex called home. The Club 57 exhibit featured psychedelic visual installations, war art propaganda, theater, film screenings. Founded by Stanley Zbigniew Strychacki, the nightclub extended an invitation to artists to exhibit their work without judgment.

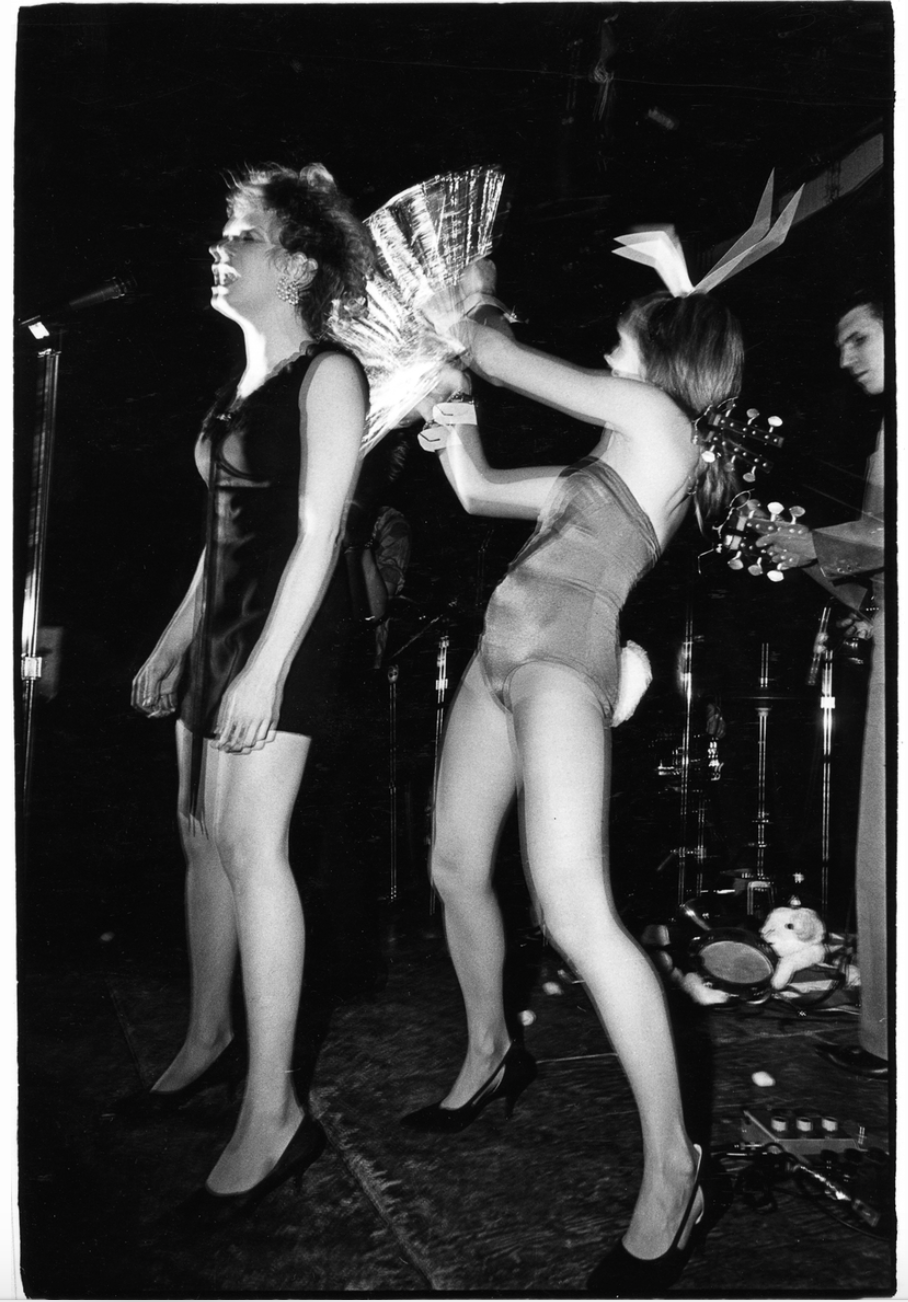

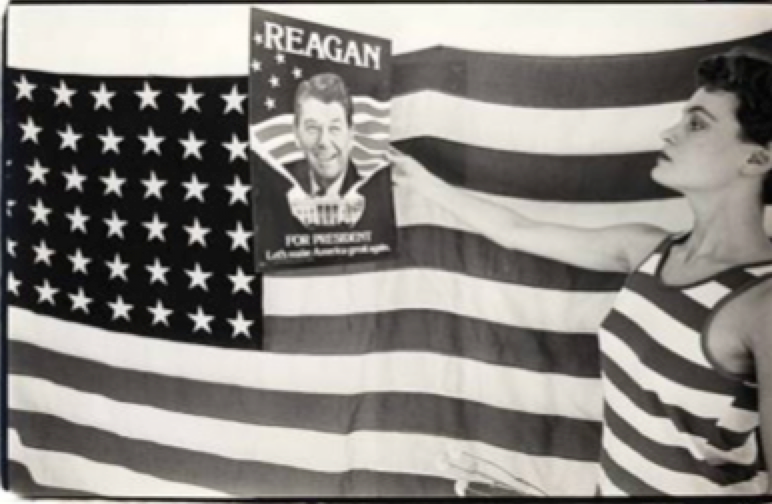

Club 57 was born out of a group of art school misfits trying to create variety in vanity. Bridging the late 70s and early 80s, New York was in the age of diversity and of new, daring art forms. Artists fueled by the AIDS epidemic, the Reagan Administration, soaring rent prices, and the War on Drugs banded together in response to the socially politicized proceedings that flooded the newspapers of the time. 57 was located in the basement of the Holy Cross Polish National Church; the vibe was unpretentious, open, and inviting. Performers, musicians, and artists of all kinds gathered together driven by the comparable dream to create new modes of music, fashion, and exhibition in the hope of promoting and establishing artistic justice.

In the midst of a chaotic political climate, visionaries gathered for an unconventional variety show where no one was turned away because of their identities. Artists in charge of selecting talent looked for themes that embodied gender, identity, punk feminism, male burlesque, and drag. All over the city, artists plastered hand-designed flyers advertising their shows, which ranged anywhere from erotic art installations to screenings of Super 8 films. Every night, Club 57 presented a new event, and every night it was packed with an audience ready for the next act to begin.

Today’s downtown Manhattan scene has changed tremendously as everyone has a different idea of what seems to be the “happening” place. After all, everyone has a different niche when it comes to going out in Manhattan. Places quickly go out of style, and then a new bar will open up that everyone wants to visit. Over the past few years spots like NeverNever and Ten June were hot for a moment but soon fizzled out. A few popular places downtown people tend to gravitate to include Berlin, Electric Room, and China Chalet. Right now, Public is one of the spots to hit. But how long will the hype last? These places are in close proximity to one another, and attract a similarly young, artsy crowd eager to share a part of themselves with the rest of their community.

One of the few places that has stood the test of time is The Pyramid Club— Situated at 101 Avenue A, right by Tompkins Square Park opened up in 1979, and was major competition to Club 57. When Andy Warhol and Debbie Harry dropped into The Pyramid for an MTV special, the Pyramid’s popularity spiked. Since then, both Nirvana and the Red Hot Chili Peppers have performed in the iconic venue. If you are nostalgic for the 80s, the Pyramid Club could certainly be the solution. At the club, they are devoted to providing guests with the full 80s experience by hosting weekly dance parties with live music and DJs.

The Pyramid and Club 57 were once the only safe spaces members of the LGBTQ+ community had. The exhibit itself was in a more hidden part of the MoMA building, in a sequestered spot in the depths of a hidden basement church in the East Village. Those who struggled with their identities felt comfortable having a place to congregate outside the politically segregated arena of the public scene. The message of acceptance proliferated by these spaces is mirrored MoMA’s recreation the space, articulating exactly the kind of progress we should be moving toward.

Originally published 12/11/17