A Long Tradition of the False Step: Situating "Red, White & Royal Blue" Amongst Its Literary Predecessors

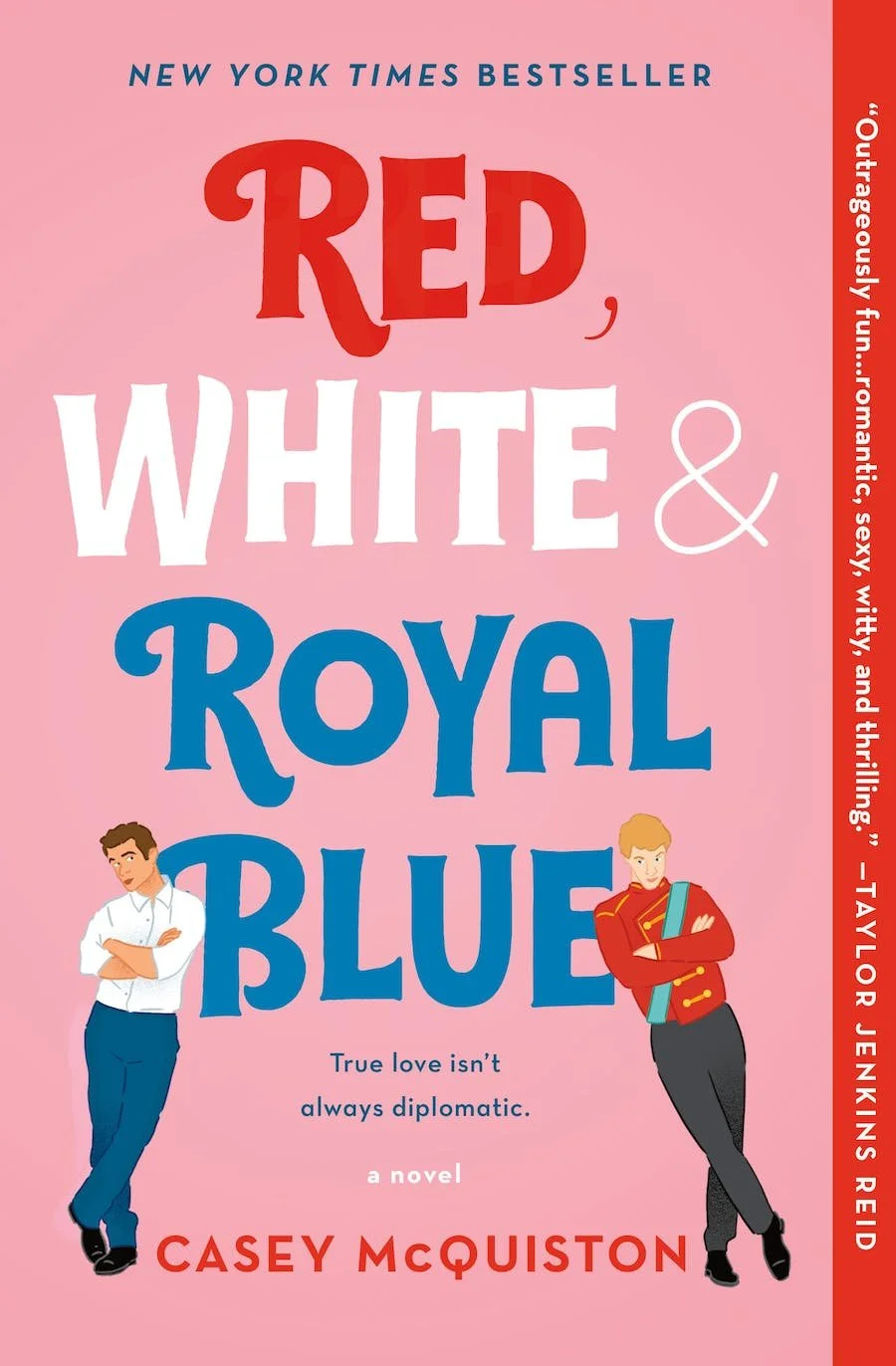

Image courtesy of Macmillan Publishers

by Jules Hasler

“What happens when America's First Son falls in love with the Prince of Wales?” is the principal question of Casey McQuiston’s debut novel, Red, White & Royal Blue. The Vogue “Best Novel of 2019” tells the story of Alex Claremont-Diaz, who, after his mother secures the presidency of the United States, becomes an “American royal.” However, his long-term rivalry with Prince Henry of Wales seems to be a threat to United States-United Kingdom relations. As a solution, a for-the-camera-only friendship is orchestrated between them, with scheduled appearances and photos to make citizens of the two nations believe that the two are best friends. However, this soon spirals into a full-fledged hidden romance that puts both the upcoming presidential election and the future of the crown at risk.

Matthew López will be making his debut as a director for the Amazon Studios film adaptation of this novel. Additionally, the director of the 2018 film Love, Simon, Greg Berlanti, will be producing the movie. Taylor Zakhar Perez and Nicholas Galitzine were cast as the leads and began filming this past summer. With an anticipated release in early 2023, many fans have already started questioning the success of the book-to-film adaptation–– myself included. How can this novel, with much of the narrative structure dependent on elaborate imagery and descriptions of the mental states of characters and not based in dialogue/physical actions, be accurately portrayed in live-action?

The novel begins with a pre-existing rivalry between two high-profile individuals in their respective countries. They are seemingly united by the notion of “a false step.” Seen frequently in the 19th century novel, McQuiston has said they drew inspiration from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice; Austen’s work is consistently mentioned throughout McQuinston’s novel itself. The false step is seen as a “faux pas,” or an action that breaks decorum involuntarily, therefore preserving the innocence of those involved. However, because such an occurrence took place, it draws two people into accidental intimacy without culpably breaking the decorum. In the 19th century tradition of relations, there were very specific rules for intimacy, and the false step was a means in novels used to draw characters into relationships with each other.

A prime example of this is seen in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, which follows three sisters, their inheritance and the character arc of a classic “libertine,” showcasing a false step very early on. Marianne, one of the three Dashwood sisters, is wandering in the rain when she falls down a hill, injuring herself upon impact. Graciously, John Willoughby–– a previously unknown character in the novel––comes to her rescue. After assessing her injuries, he voluntarily “took her up in his arms without farther delay, and carried her down the hill,” taking her back to the comfort of her home. Marianne and John’s intimacy following this interaction would have been impossible were it not for the accidental breach of decorum. In the time of Austen’s novel, as evident in the book and other 18th and 19th century novels, women did not have the power of initiation or input in relationships whatsoever. They merely had the power of refusal; therefore, in order to develop relationships, female characters were often made victims of these “false steps'' to serve as a form of accidental initiation. There is a linear connection between a false step and dangerous intimacy. In the case of Marianne and Willoughby, their relationship was deemed “dangerous” because the financial component of marriage in their time negated their relationship, and eventually led to a form of heartbreak and separation for both of them.

The false step trope can also be seen in the 18th century novel Clarissa, by Samuel Richardson. In this case, the titular character’s initial false step was her decision to run away with the libertine, Robert Lovelace. However, a further development of this falsity is shown through the epistolary form of the novel— Clarissa is secretly communicating through letters that eventually get intercepted, revealing Robert’s drastic breach of decorum.

The initial false steps in these two examples seem to be physical actions, but is the true falsity more situational? In both examples, we see literal “false steps”— the slip of a foot, or a plan to run away— which act as the cover for very intentional action. In the case of Marianne and Willoughby, though their intimacy was initiated by Marianne’s clumsiness, the two make the conscious decision to continue their relations beyond one event. Alex and Henry are seen as “rival royals” of their respective countries, and are contracted into a friendship to maintain the look of public relations between the United States and United Kingdom as a result. The physical false step occurs when Alex trips over Henry, causing them to fall on top of each other. The two are forced to have a genuine conversation while stuck, sparking the rest of what develops between them. This physical false step generates the emotional false step to follow. After their relationship develops into something romantic, Henry and Alex begin communicating via emails, a modern day form of the letters exchanged in Clarissa.

The epistolary subplot of Red, White & Royal Blue was a very popular idea in the 18th and 19th century novel. I believe that putting feelings into words and onto a page––whether it be written or typed––is the ultimate false step for the romance novel because it is the most dangerous way of breaking decorum. In the case of Red, White & Royal Blue, a prince being gay, along with entertaining a relationship with such a prominent figure of another country, would be highly against decorum. Therefore, their entire relationship was forced into secrecy. The email correspondence between Alex and Henry seems to have been inspired from the interception of letters in Clarissa, because these emails do eventually get exposed to the public.

This comparison between the relationship of Alex and Henry to the relationships in an 18th or 19th century novel is interesting for the power dynamics it introduces. In the 18th and 19th century, the man had the power in the relationship; the woman merely had the power of refusal when a man offered a relationship, per the decorum of the time. This seems to be similar in the case of Henry and Alex— though it’s obviously not quite the same considering the struggles of an 18th and 19th century heterosexual relationship are incredibly different from a closeted gay relationship in almost any time period. Alex, coming from a family who supports him and a culture which is more accepting of his sexuality, would be able to safely come out to the public. Henry, however, consistently and clearly explains that the dynamic of the royal family means he isn’t allowed to be gay. Henry, therefore, has to be the one to approach Alex with advancements in the relationship, and Alex merely had the power of refusal. This idea of the “false step” enters the equation because it is a manner in which the character who can only refuse is able to initiate advancements in the relationship without the social repercussions.

How might this “physical false step” be portrayed in the film adaptation? Many times, the narrative structure of a novel conveys the tension of this false step by heightening the charge of the situation in its description. However, this is sometimes difficult to portray in a film adaptation, so the directors often take creative liberties.

Drawing on Sense and Sensibility, the 1995 movie’s version of Marianne’s false step is quite different from that of Austen’s original words. The movie shows Willoughby rescuing Marianne and follows it with a scene of him giving her a foot massage (which did not happen in the book). The director of the movie took this liberty in order to show the tension in a physical way that was not conveyed in the original dialogue of the book––only between the lines. How might López adjust the parallel scene in Red, White & Royal Blue? Personally, I don’t think any adjustments need to be made; McQuiston wrote the encounter explicitly creating a “false step” which could be very directly translated into film, and I hope that López appreciates and leans into the trope.

The progression of novel to film is a fine line. How can a film be adapted from a book that represents what is lost with the lack of narrative language, while also maintaining the integrity of the novel? With a common scene like the “false step,” there is promise that with a surplus of examples to follow, the film adaptation of Red, White & Royal Blue will deliver just as much as the book itself did.